Margaret Beaufort (Br [ˈbɛʊfɨt][1]), Countess of Richmond and Derby (31 May 1443 – 29 June 1509) was the mother of King Henry VII and paternal grandmother of King Henry VIII of England. She was a key figure in the Wars of the Roses and an influential matriarch of the House of Tudor. She founded two Cambridge colleges.

Contents

[hide]- 1 Early life

- 2 Marriages

- 3 The King's Mother

- 4 Death

- 5 Legacy

- 6 Portraits

- 7 Titles, styles, honours and arms

- 8 In historical fiction

- 9 In film

- 10 Ancestors

- 11 Notes and references

- 12 Bibliography

- 13 External links

Lady Margaret Beaufort Lady Margaret Beaufort at prayer.Born 31 May 1443

Bletsoe Castle, Bedfordshire,EnglandDied 29 June 1509 (aged 66)

London, EnglandTitle Countess of Richmond and Derby Spouse(s) Edmund Tudor, 1st Earl of Richmond

Sir Henry Stafford

Thomas Stanley, 1st Earl of DerbyChildren Henry VII of England Parents John Beaufort, 1st Duke of Somerset

Margaret Beauchamp of BletsoeMargaret Beaufort (Br [ˈbɛʊfɨt][1]), Countess of Richmond and Derby (31 May 1443 – 29 June 1509) was the mother of King Henry VII and paternal grandmother of King Henry VIII of England. She was a key figure in the Wars of the Roses and an influential matriarch of the House of Tudor. She founded two Cambridge colleges.Contents

[hide]Early life

Margaret was born at Bletsoe Castle, Bedfordshire, on 31 May 1443 or 1441. The date and month are not disputed, as she required Westminster Abbey to celebrate her birthday on 31 May. The year of her birth is more uncertain. William Dugdale, the 17th century antiquary, has suggested that she may have been born two years earlier, in 1441. This

Early life

Margaret was born at Bletsoe Castle, Bedfordshire, on 31 May 1443 or 1441. The date and month are not disputed, as she required Westminster Abbey to celebrate her birthday on 31 May. The year of her birth is more uncertain. William Dugdale, the 17th century antiquary, has suggested that she may have been born two years earlier, in 1441. This suggestion is based on evidence of inquisitions taken at the death of Margaret's father. Dugdale has been followed by a number of Margaret's biographers. However, it is more likely that she was born in 1443, as in May 1443, her father had negotiated with the King about the wardship of his unborn child in case he died on a campaign.[2]

She was the daughter of Margaret Beauchamp of Bletsoe and John Beaufort, 1st Duke of Somerset. Margaret's father was a great-grandson of King Edward III through his third-surviving son, John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster. At the moment of her birth, Margaret's father was preparing to go to France and lead an important military expedition for King Henry VI. Somerset negotiated with the king to ensure that, in case of his death, the rights to Margaret's wardship and marriage would belong only to his wife. Somerset fell out with the king after coming back from France, however, and he was banished from the court and was about to be charged with treason. He died shortly afterwards. According to Thomas Basin, Somerset died of illness, but the Crowland Chronicle reported that his death was suicide. Margaret, as his only child, was the heiress to his fortunes.[3]

On Margaret's first birthday, the King broke his arrangement with Margaret's father and gave her wardship to William de la Pole, 1st Duke of Suffolk, although Margaret remained with her mother. Margaret's mother was pregnant at the time of Somerset's death, but her sibling did not survive and Margaret remained sole heir.[4] Although she was her father's only legitimate child, Margaret had two half-brothers and three half-sisters from her mother's first marriage, whom she supported after her son's accession.[5]

Marriages

First marriage

Margaret was married to Suffolk's son, John de la Pole. The wedding may have been held between 28 January and 7 February 1444, when she was perhaps, a year old, but certainly, no more than three. However there is more evidence to suggest they were married in January 1450 after Suffolk had been arrested and was looking to secure his son's future. Papal dispensation was granted on 18 August 1450 because the spouses were too closely related and this concurs with the later date of marriage.[6] Three years later, the marriage was dissolved and King Henry VI granted Margaret's wardship to his own half-brothers, Jasper and Edmund Tudor.[7][8][9] Margaret never recognised this marriage. In her will, made in 1472, Margaret refers to Edmund Tudor as her first husband. Under canon law, Margaret was not bound by the marriage contract as she was entered into the marriage before reaching the age of twelve.[7]

Second marriage

Even before the annulment of her first marriage, Henry VI chose Margaret as a bride for his half-brother, Edmund Tudor, 1st Earl of Richmond. Edmund was the eldest son of the king's mother,Dowager Queen Catherine (of Valois,) by Owen Tudor.[7]

Margaret was 12 when she married 24-year old Edmund Tudor on 1 November 1455. The Wars of the Roses had just broken out; Edmund, a Lancastrian, was taken prisoner by Yorkist forces less than a year later. He died of the plague in captivity at Carmarthen the following November, leaving a 13-year-old widow who was seven months pregnant with their child.

Taken into the care of her brother-in-law Jasper, at Pembroke Castle, the Countess gave birth on 28 January 1457 to her only child, Henry Tudor, the future Henry VII of England. The birth was particularly difficult; at one point, both the Countess and her child were close to death, due to her young age and small size. After this difficult birth she would never give birth again.[10]

Margaret and her son remained in Pembroke until the York triumphs of 1461 saw the castle pass toLord Herbert of Raglan.[11] From the age of two, Henry lived with his father's family in Wales and from the age of fourteen, he lived in exile in France. During this period, the relationship between mother and son was sustained by letters and a few visits.[12]

The Countess always respected the name and memory of Edmund, as the father of her only child. In 1472, sixteen years after his death, Margaret specified in her will that she wanted to be buried alongside Edmund, even though she had enjoyed a long, stable and close relationship with her third husband, who had died in 1471.[citation needed]

Third marriage

On 3 January 1462, Margaret married Sir Henry Stafford (c.1425–1471), son of Humphrey Stafford, 1st Duke of Buckingham. A dispensation for the marriage, necessary because Margaret and Stafford were second cousins, was granted on 6 April. The Countess enjoyed a fairly long and harmonious marital relationship during her marriage to Stafford. Margaret and her husband were given 400 marks worth of land by Buckingham, but Margaret's own estates were still the main source of income. They had no children.[13]

She became a widow again in 1471.[citation needed]

Fourth marriage

In June 1472, Margaret married Thomas Stanley, the Lord High Constable and King of Mann. Their marriage was at first a marriage of convenience. Recent historians have suggested that Margaret never considered herself a member of the Stanley family.[14]

She conspired against Richard III with the dowager queen, Elizabeth Woodville. As Elizabeth's sons, the Princes in the Tower, were presumed murdered, the two women agreed on the betrothal of Margaret's son, Henry, to Elizabeth of York, the eldest daughter of Edward IV and his wife Elizabeth Woodville; thus Henry became king Henry VII.[citation needed]

Margaret's husband also secretly conspired against Richard. When summoned to fight at the Battle of Bosworth Field in 1485, Thomas Stanley stayed aloof from the battle, even though his eldest son, George Stanley (styled Lord Strange), was held hostage by Richard. After the battle, it was Stanley who placed the crown on the head of his stepson (Henry VII), who later made him Earl of Derby. Margaret was then styled "Countess of Richmond and Derby".[citation needed]

Later in her marriage, the Countess preferred living alone. In 1499, with her husband's permission, she took a vow of chastity in the presence of Richard FitzJames, Bishop of London. Taking a vow of chastity while being married was unusual, but not unprecedented, as around 1413, Margery Kempealso negotiated a vow of chastity with her husband. The Countess moved away from her husband and lived alone at Collyweston. She was regularly visited by her husband, who had rooms reserved for him. Margaret renewed her vows in 1504.[15]

The King's Mother

After her son won the crown at the Battle of Bosworth Field, the Countess was referred to in court as "My Lady the King's Mother". As such, she enjoyed legal and social independence which other married women could not (see Coverture). Her son's first parliament recognised her right to hold property independently from her husband, as if she were unmarried.[16]Towards the end of her son's reign she was given a special commission to administer justice in the north of England.[17]

As arranged by their mothers, Henry married Elizabeth of York. The Countess was reluctant to accept a lower status than the dowager queen Elizabeth or even her daughter-in-law, thequeen consort. She wore robes of the same quality as the queen consort and walked only half a pace behind her.[citation needed]

Margaret had written her signature as M. Richmond for years, since the 1460s. In 1499, she changed her signature to Margaret R., perhaps to signify her royal authority (R standing either for regina – queen in Latin as customarily employed by female monarchs – or for Richmond). Furthermore, she included the Tudor crown and the caption et mater Henrici septimi regis Angliæ et Hiberniæ ("and mother of Henry VII, king of England and Ireland").[18][19]

Many historians believe the departure from court of dowager queen Elizabeth Woodville in 1487 was partly at the behest of Henry's influential mother, though this is uncertain.[20] The Countess was known for her education and her piety, and her son is said to have been devoted to her. He died on 21 April 1509, having designated his mother chief executor of his will. She arranged her son's funeral and her grandson's coronation. At her son's funeral she was given precedence over all the other women of the royal family.[citation needed]

Death

The Countess died in the Deanery of Westminster Abbey on 29 June 1509. This was the day after her grandson's 18th birthday and just over two months after the death of her son. She is buried in the Henry VII Lady Chapel of the Abbey, in a black marble tomb topped with a bronze gilded effigy and canopy, between the graves of William and Mary and the tomb of Mary, Queen of Scots.[citation needed]

Legacy

In 1497 she announced her intention to build a free school for the general public of Wimborne, Dorset. With her death in 1509, Wimborne Grammar School, now Queen Elizabeth's School, came into existence.[citation needed]

In 1502 she established the Lady Margaret's Professorship of Divinity at the University of Cambridge.[citation needed]

In 1505 she refounded and enlarged God's House, Cambridge as Christ's College with a royal charter from the king. She has been honoured ever since as the Foundress of the College. A copy of her signature can be found carved on one of the buildings (4 staircase, 1994) within the College. In 1511, St. John's College, Cambridge was founded by her estate, either at her direct behest or at the suggestion of her chaplain, St. John Fisher. Land that she owned around Great Bradley in Suffolk was bequeathed to St. John's upon its foundation. Her portrait hangs in the Great Halls of both Christ's and St. John's, accompanied by portraits of St. John Fisher. Both Colleges also have her crest and motto as the College arms. Furthermore, various societies, including the Lady Margaret Society as well as the Beaufort Club at Christ's, and the Lady Margaret Boat Club at John's, were named after her.[citation needed]

Lady Margaret Hall, the first women's college at the University of Oxford, was named in her honour.[citation needed]

She funded the restoration of Church of All Saints, Martock and the construction of the church tower.[21]

There is a school named after her in Riseley, Bedfordshire.[citation needed]

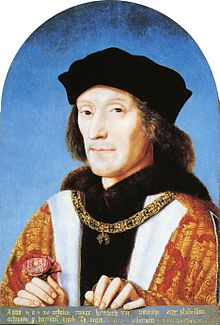

Portraits

There is no surviving portrait of Margaret Beaufort dating from her lifetime. All known portraits, however, are in essentially the same format, depicting her in her later years, wearing a long, peaked, white headress and in a pose of religious contemplation. Most of these were made in the reign of Henry VIII and Elizabeth I as symbols of loyalty to the Tudor regime. They may be based on a lost original, or be derived from Pietro Torrigiano's sculpture of Margaret on her tomb in Westminster Abbey, in which she wears the same headdress.[22] Torrigiano, who probably arrived in England in 1509, was commissioned to make the sculpture in the following year.[23]

One variant by Rowland Lockey shows her at prayer in her richly furnished private closet behind her chamber. The plain desk at which she kneels is draped with a richly-patterned textile that is so densely encrusted with embroidery that its corners stand away stiffly. Her lavishly illuminated Book of Hours is open before her, with its protective cloth wrapper (called a "chemise" binding), spread out around it. The walls are patterned with oak leaf designs, perhaps in lozenges, perhaps of stamped and part-gilded leather. Against the wall hangs the dosser of her canopy of estate, with the tester above her head (the Tudor rose at its centre) supported on cords from the ceiling. The coats-of-arms woven into the tapestry are of England (parted as usual with France) and the portcullis badge of the Beauforts, which the early Tudor kings later used in their arms. Small stained glass roundels in the leaded glass of her lancet windows also display elements of the arms of both England (cropped away here) and Beaufort.[citation needed]

Titles, styles, honours and arms

Titles and styles

- 1443-1455: Lady Margaret Beaufort

- 1455-1456: The Countess of Richmond

- 1456-1462: Dowager Countess of Richmond

- 1462-1471: Lady Stafford (Also informally, Dowager Countess of Richmond)

- 1472-1485: Baroness Stanley

- 1485-1509: The Countess of Richmond and Derby (Also informally as My Lady The King's Mother)

In historical fiction

- Betty King, The Lady Margaret, pub 1965, a story about the marriage of Margaret Beaufort and Edmund Tudor, parents of King Henry VII

- Betty King, The King's Mother, pub 1969, sequel to the above, the story of the widowed Margaret Beaufort. mother of the future King Henry VII

- Iris Gower, Destiny's Child. 1999. This novel was originally published in 1974 as Bride of the Thirteenth Summer, under the name Iris Davies.

- Philippa Gregory, The Constant Princess, a story about the young Catherine of Aragon and her early life in England

- Philippa Gregory, The White Queen, pub 2009, (Book 1 in the Cousins' War series – about Elizabeth Woodville)

- Philippa Gregory, The Red Queen, pub 2010, (Book 2 in the Cousins' War series – about Margaret Beaufort herself)

- Philippa Gregory, The Kingmaker's Daughter, pub 2012, (Book 4 in the Cousins' War series – about Anne Neville)

- Philippa Gregory, The White Princess, pub 2013, (Book 5 in the Cousins' War series – about Elizabeth of York)

In film

The character of Lady Margaret, portrayed by Marigold Sharman, appears in eight episodes of the BBC miniseries Shadow of the Tower, opposite James Maxwell as her son Henry VII. She is portrayed as a woman of extreme ambition and piety, with a hint of ruthlessness for those who stand in the way of the Tudor Dynasty.

Channel 4 and RDF Media produced a drama about Perkin Warbeck for British television in 2005, Princes in the Tower. It was directed by Justin Hardy and starred Sally Edwards as Lady Margaret, opposite Paul Hilton as Henry VII, Mark Umbers as Warbeck, and Nadia Cameron Blakey as Elizabeth of York. In this drama, Margaret is depicted as the power behind the throne, a hardened woman of fanatical devotion to both God and herself. She is referenced as a victim of abuse and power who, used by men all her life, became as ruthless and callous as those around her.

In 2013, Amanda Hale portrayed Lady Margaret Beaufort in the television drama series, The White Queen, which will be shown on BBC One, Starz, and VRT.

Ancestors

Through her father, Lady Margaret Beaufort was a granddaughter of John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset, a great-granddaughter of John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster and his mistress and third wife Katherine Swynford, and a great-great-granddaughter of King Edward III of England.

Following Gaunt's marriage to Katherine, their children (the Beauforts) were legitimised, but the legitimation carried a condition: their descendants were barred from inheriting the throne. Lady Margaret's own son Henry VII (and all English, British, and UK sovereigns who followed) are descended from Gaunt and Swynford, Henry VII having come to the throne not through inheritance but by force of arms.

Margaret's ancestors in three generations

| John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster | |||||||||

| John Beaufort, 1st Earl of Somerset | |||||||||

| Katherine Swynford | |||||||||

| John Beaufort, 1st Duke of Somerset | |||||||||

| Thomas Holland, 2nd Earl of Kent | |||||||||

| Margaret Holland | |||||||||

| Alice FitzAlan | |||||||||

| Lady Margaret Beaufort | |||||||||

| Sir Roger Beauchamp | |||||||||

| John, Baron Beauchamp of Bletso | |||||||||

| Mary Beauchamp | |||||||||

| Margaret Beauchamp of Bletso | |||||||||

| Sir John Stourton | |||||||||

| Edith Stourton | |||||||||

| Jane Basset | |||||||||

Notes and references

- ^ "Beaufort", and "Pronunciation Guide", §22, in Webster's Biographical Dictionary (1943), Springfield, MA: Merriam-Webster.

- ^ Jones & Underwood, 34.

- ^ Jones & Underwood, 35.

- ^ Jones & Underwood, 35–36.

- ^ Jones & Underwood, 33.

- ^ Gristwood, Sarah (2012). Blood Sisters. p. 36.

- ^ a b c Jones & Underwood, 37.

- ^ Richardson, Henry Gerald;, Osborne Sayles, George (1993).The English Parliament in the Middle Ages. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-9506882-1-5. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- ^ Wood, Diana (2003). Women and religion in medieval England. Oxbow. ISBN 1-84217-098-8. Retrieved 25 July 2009.

- ^ Jones & Underwood, 40.

- ^ David Lourdes(2012) The Tudors:History of a Dynasty p3

- ^ Krug, 84.

- ^ Jones & Underwood, 41.

- ^ Jones & Underwood, 144.

- ^ Jones & Underwood

- ^ Jones & Underwood, 187.

- ^ Barbara J. Harris, “Women and Politics in Early Tudor England,” The Historical Journal, 33:2, 1990, p.259.

- ^ Jones & Underwood, 292.

- ^ Krug, 85.

- ^ Arlene Okerlund, Elizabeth: England's Slandered Queen, Stroud: Tempus, 2006, 245.

- ^ Robinson, W.J. (1915). West Country Churches. Bristol: Bristol Times and Mirror Ltd. pp. 6–10.

- ^ Strong, Roy, Tudor & Jacobean Portraits, The National Portrait Gallery, London 1969, p.20

- ^ Wyatt, Michael, The Italian Encounter with Tudor England: A Cultural Politics of Translation, Cambridge University Press, 2005, p.47.

- ^ Boutell, Charles (1863). A Manual of Heraldry, Historical and Popular. London: Winsor & Newton. p. 146.

ไม่มีความคิดเห็น:

แสดงความคิดเห็น